On August 4th, 1962, Marilyn Monroe died by suicide after taking an overdose of prescription medication. Everything written about her life afterwards was coloured by that tragic ending.

The pressures of fame, the commodification of her beauty, and the constant presence in her life of people who saw her as an easy pathway to fame and wealth were her downfall. Coupled with an often lonely upbringing in the foster care system, her years as Hollywood’s biggest star were seen as a curse rather than a fairytale, and her violent death has often been treated as an inevitability.But in 1958, four years before she died, a film was released that was based on Monroe’s life without being beholden to its tragic end. Directed by John Cromwell and written by Paddy Chayefsky, who had won an Oscar for Marty and would go on to win two more for The Hospital and Network, The Goddess starred Kim Stanley in her film debut as Emily Ann Faulkner, a young woman from a broken home in the south who becomes a Hollywood star named Rita Shawn.

Stanley claimed that Monroe was not the inspiration behind the character, but the parallels are too overt to be denied. Emily Ann Faulkner sounds a lot like Norma Jean Baker. Both the character in the film and Monroe were born to single mothers who weren’t sure who the father was and were ill-equipped to take care of their child. Both married while still teenagers and divorced their first husbands in order to pursue a career in Hollywood. Both married a retired famous sports star, and both struggled with addiction, mental breakdowns, and suicide attempts. And both, of course, were brunettes who became blonde.The Goddess takes a sweeping approach to Rita’s story, splitting the narrative into three sections: ‘Portrait of a Young Girl’, ‘Portrait of a Young Woman’, and ‘Portrait of a Goddess’. What emerges, as has been the case with most Monroe biographies and biopics, is a clear thesis. In this case, that thesis is the inescapability of childhood trauma. We watch Emily Ann grow up unwanted by her mother, mournfully looking for someone to tell when she excels in school and having to resort to talking to a stray cat. As a teenager, she gains a reputation for promiscuity because she will do anything to experience some kind of affection. Her first husband is just like her, a lost soul desperate for affection whose self-esteem is so low that he doesn’t trust or respect anyone who offers him love. Arthur Miller, who was married to Monroe at the time the film was released, supposedly said that he thought Monroe should sue for libel. The film opts to ignore Rita’s work life entirely and focus only on her personal relationships. We see her tortured relationship with her disinterested mother, disastrous relationships with her husbands, and her painful experience as a young mother (a significant deviation from Monroe’s story). After abandoning her infant daughter with her first husband, she finds no friends in Hollywood except predatory studio executives who crave the combination of sensuality and warmth that she supposedly emanates.

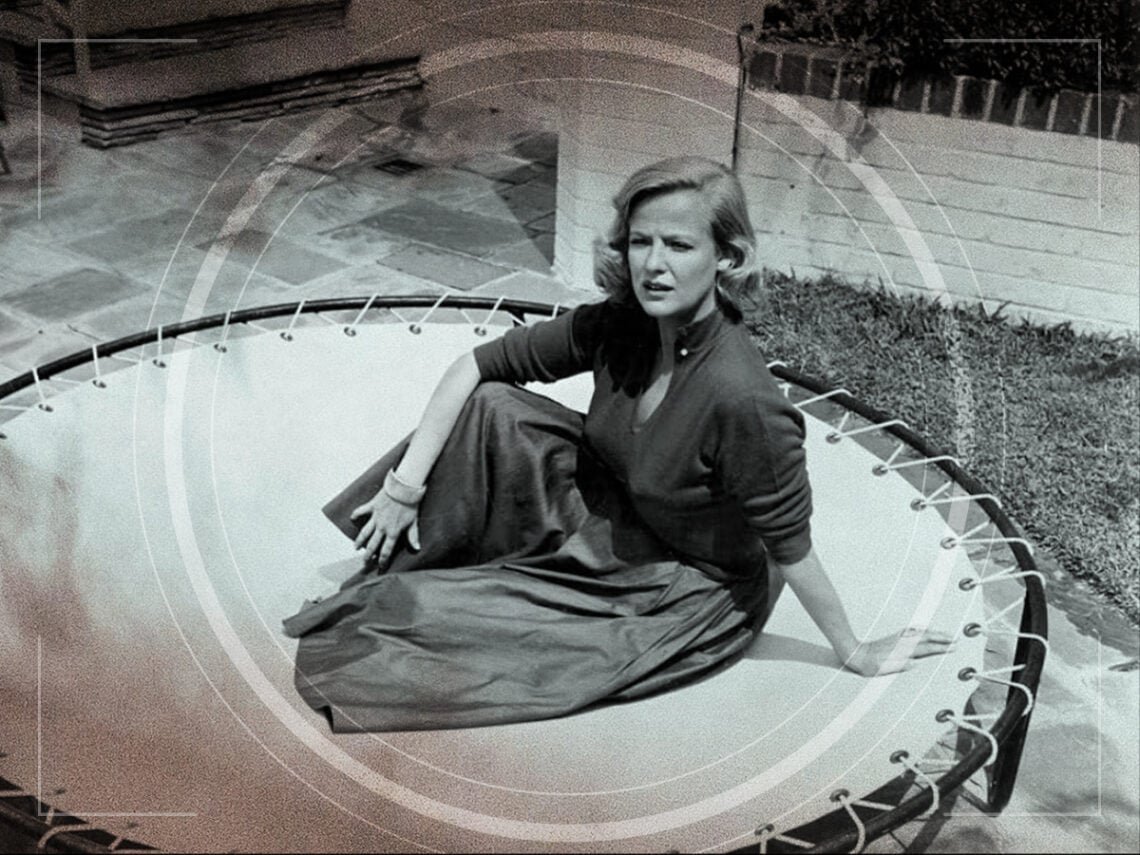

Stanley’s performance drives the picture, and it is at turns heartbreakingly subtle and melodramatic, straying into Blanche DuBois territory during particularly heated moments. Stanley had firsthand experience of Monroe, having been a student of the Actor’s Studio in New York at the same time, and it’s clear that she had a distinct impression of the character she was playing. Rita is gentle and childlike, with a breathiness that sounds exactly like the Seven Year Itch star with the addition of a light Southern drawl. She is also self-absorbed to the point where the film can feel stifling. Not only is Rita in nearly every frame, but her emotion is the only source of mood.

Although The Goddess was her film debut, Stanley was already a critically acclaimed television and theatre star and had even originated the lead character in the play Bus Stop in 1955, which became Monroe’s first film after training at the Actor’s Studio. Stanley came to despise The Goddess due to Cheyefsky’s meddling in the editing process. Cromwell, too, despaired. The writer had next to no experience in the editing room but insisted on having the final cut.

Stanley and Cromwell blamed the film’s many failures on Cheyefsky’s editing, with the actor saying that it was “my least favourite out of any work I’ve ever done”. She claimed that Cheyefsky had “left out all the comedic stuff, and it broke my heart because nobody doesn’t try to laugh once in a while. I mean, no fooling! Little Orphan Annie in Hollywood is really not interesting.” The main failure of the film, though, is in its moralistic approach to Rita’s situation. The people around her are not treated like the leeches and opportunists that haunted Monroe’s final decade. Many of them are portrayed as benevolent figures who want to help. By the end of the film, her first husband expresses a desire to reconnect with her and reintroduce her to their daughter. He claims that he has healed himself by giving their child a healthy, happy childhood, breaking the cycle of loneliness and neglect that ruined him and Rita. In the final scene, Rita refuses to go with him, and he walks across the street to embrace their daughter as if to show that, even though Rita is a lost cause, their child isn’t destined for a similarly tragic end.It’s a strangely bleak, finger-wagging ending, suggesting that he has moved on from his damaged childhood by finding purpose in parenthood while she, having chosen the hollow successes of fame, is unfixable and irredeemable. To put a finer point on it, the film may as well end with a voiceover telling the audience to embrace motherhood over career aspirations, and since it never actually shows her working, there is no reason to believe that the work is important.

Ultimately, The Goddess is a fascinating glimpse at how the public and the filmmakers viewed Monroe during the period when her career was on its last legs. She is both a subject of pity and a subject of scorn. Her constant pleas for love are painfully simplistic and on the nose, even as the first part of the film tries to show, rather than tell, why she became so unfulfilled as an adult. There is surprisingly little to connect to with the character. There is none of the charisma or warmth that Monroe had in spades, nor is there a meaningful examination of her intelligence, genuine ambition as an actor, or weakness for authoritarian hangers-on.

The Goddess can be seen as the first failure to analyse the real person behind the Monroe myth, a trendsetter of sorts. Movies like Blonde might take an even more repulsive and exploitative approach, while My Week With Marilyn attempts a softer, more direct rendering of a particular period in her life, but no film based on Monroe has ever justified its existence.